In the last two posts, we explored the theory behind the Jacobian inverse method for solving the inverse kinematics of a system:

Inverse kinematics using the Jacobian inverse, part 1 Inverse kinematics using the Jacobian inverse, part 2

It’s assumed that you’ve either read those posts or already have a good understanding of how the Jacobian inverse method works. As the title suggests, this post has two major goals:

- To animate the Jacobian inverse method in Python and visualize its limitations.

- To learn about creating interactive plots in matplotlib.

The end result

This video demonstrates the Jacobian inverse method in action. The dashed circle represents the maximum reach of the arm, which is based on the lengths of all the individual links. We see that it works for any arbitrary number of joints, and we get an idea of how it tracks a moving target when the end effector is made to move at a constant velocity. We also see one of its major drawbacks, which is its instability at singularities—notice how, when the target is outside the reach of the arm, or when the location of the target forces the arm to straighten out, the joint angles change suddenly and erratically. There are several alternatives and improvements to the Jacobian inverse method that address these issues, but we won’t get into those in this post. Instead, we’ll see how to produce the animations from the video in Python.

The code, part 1

We will create two files, RobotArm.py and jacobianInverse.py, which you can find on Github.

First, create a file named RobotArm.py, or get it from the Github link above.

|

|

We start by defining a class, RobotArm2D. This class will contain the joint

angles of our robot arm, the Cartesian coordinates of each joint and the end

effector, and the length of each link of the arm. Note that, even though our

robot arm exists in two dimensions (the XY plane), we’ll use a 3D

representation in our code, not only because this will be more generalizable in

case we wish to extend our system to three dimensions, but also because

it’ll simplify some of the math, namely the use of cross products.

Technically, we’re working in 4D—our position vectors contain a

dummy fourth coordinate for use with 4×4 transformation matrices, which

perform both rotation and translation.

The __init__() method of our class, i.e., the constructor, has two optional

keyword arguments: xRoot and yRoot. These set the location of the root

joint, i.e., the first joint of the robot arm. If omitted, they default to 0,

which is accomplished by the get() method of the kwargs dictionary. Class

instantiation in Python via the __init__() method, as well as functions of a

class, are discussed in a little more detail in this blog’s very first

post, titled Visualizing K-means clustering in 1D with Python. We also

initialize the 1D array thetas, which will contain the joint angle of each

joint, and the 2D array joints, in which each column will be a 4D position

vector representing the coordinates of a joint. The first column in joints

will be the root joint and the last column will be the end effector. Finally,

lengths is a list that will contain the length of each link.

|

|

To actually add joints/links to our robot arm, we define the function

add_revolute_link(). Note that this allows us to add any arbitrary number of

joints. Only the length of the link corresponding to the added joint is

required. The initial angle can be specified if desired. The end of the last

link is taken to be the end effector.

|

|

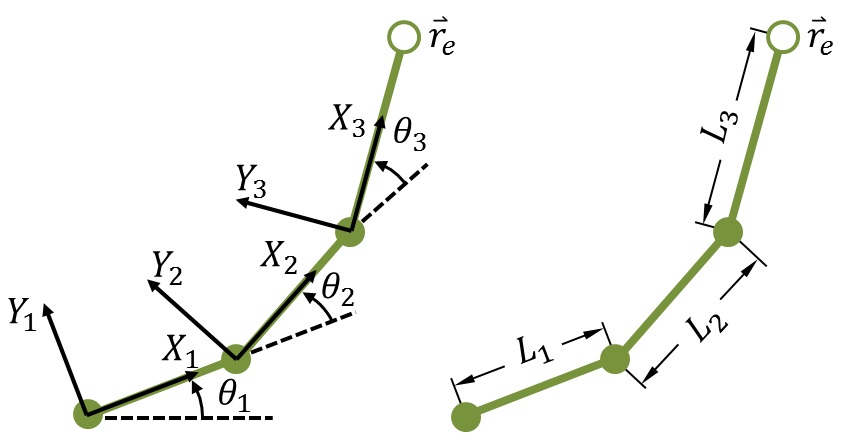

The function get_transformation_matrix() will be used to get 4×4 the

transformation matrix corresponding to each joint’s coordinate system. The

coordinate systems (and resulting transformation matrices) for the arm are

defined as in this previous post:

|

|

The function update_joint_coords() updates the coordinates in joints based

on the angles in thetas. The function works its way up from root joint to end

effector. The transformation matrix for converting coordinates from the root

joint coordinate system (“1”) to the global coordinate system

(“0”) is \([^0 T_1]\). The coordinates of the root joint, in the

first column of joints, are given by xRoot and yRoot and do not change.

The transformation matrix to convert from the second joint’s coordinate

system (“2”) to the root joint coordinate system (“1”)

is \(\left[^1 T_2\right]\). To convert from the second joint system to the global system,

these matrices are multiplied:

\(\left[ ^0 T_2 \right] = \left[ ^0 T_1 \right] \left[^1 T_2\right]\). This is

what lines 63-65 accomplish. For each \(i^{th}\) iteration, the transformation

matrix from the previous iteration (which converts from system \(i-1\) to

the global system) is multiplied with the transformation matrix from the current

iteration (which converts from system \(i\), i.e., the current joint, to system

\(i-1\), i.e., the previous joint). For the third joint, lines 63-65

would take the transformation matrix \(\left[ ^0 T_2 \right]\) and multiply it with the

transformation matrix for the third joint, \(\left[ ^2 T_3 \right]\):

\(\left[ ^0 T_3 \right] = \left[ ^0 T_2 \right] \left[ ^2 T_3 \right]\). In

this way, the coordinates of each successive joint are

converted to the global coordinate system. Since we’ve defined the end

effector to be a vector in the final coordinate system, we multiply that vector

by the final transformation matrix to get its coordinates in the global system.

As a side note, observe on line 66 that I enclosed the second index of

joints in brackets: self.joints[:,[i+1]]. The reason for this is to preserve

the shape of the original array. That bit of code extracts all rows of column

i+1 as a two-dimensional, 4×1 array. If, instead, we’d used

self.joints[:, i+1], that column would have been “flattened” into

a 1D array of 4 elements, potentially leading to incompatibilities when trying

to multiply it or add it to other arrays. This is an important thing to note

about numpy arrays: an array of shape (4,1) is 2D, and is not the same as an

array of shape (4,), which is 1D, even though both arrays contain 4 elements.

|

|

The function get_jacobian() utilizes the cross product to compute each column

of the Jacobian matrix (see the previous post for more on this), using the

unit vector pointing along the axis of rotation for each joint. In our

simplified 2D case, the axis of rotation for every joint points along the \(Z\)

axis, i.e., \(\hat{k}\).

|

|

The last part of the class is a function, update_theta(), that does exactly

what the name suggests. We use the flatten() method of the input array to

“flatten” it to a 1D array, so we can add it to the 1D thetas

array.

The code, part 2

Now, we’ll utilize the class we just created to animate the algorithm using an interactive plot. Create a file named jacobianInverse.py, or get it on Github.

|

|

First, the necessary imports, including the file we created in the last section. We create an instance of the class, add several joints, update the joint coordinates, and initialize the target location to the initial end effector location.

|

|

Next, we create the plot. The argument figsize=(5,5) to plt.subplots() on

line 19 sets the figure size; in this case, the goal is simply to set the

height and width equal so the figure is square. On line 20, we use

subplots_adjust() to position the axis limits at the edges of the figure, so

the axes take up the entirety of the plot.

|

|

Now, we compute the reach of the arm and use it to set the axis limits, with some white space at the edges, then plot a circle to indicate the boundaries of the arm’s reach.

|

|

Lines 36-41 define a function, update_plot(), to update the coordinates of

the arm and end effector plot objects. Line 43 runs this function to

initialize these plot objects with the coordinates from the arm object.

|

|

The function move_to_target() actually performs the Jacobian inverse

technique, or at least one iteration of it. Line 50 sets how far to move the

end effector on each iteration (each update of the arm’s position), as a

fraction of the arm’s reach, which essentially scales the arm’s

motion to its total length. Basically, this sets the velocity of the end

effector, if you think of each iteration as a unit of time, as long as the end

effector is farther from the target than the distance specified by line 52

(if it’s closer, then it’s considered sufficiently close, and

doesn’t move). On lines 53-54, we get the unit vector in the direction

of the target from the end effector. On line 55, we compute \(\Delta \mathbf{r}\),

or the vector distance that we’d like the end effector to move (toward the

target). The rest of the function computes the Jacobian based on this vector,

inverts the Jacobian, computes the change in joint angles, then updates the

joint coordinates and the plot with the new arm configuration.

|

|

Now, we arrive at the interactive stuff. First, we define the variable mode,

which will assume a value of 1 or -1. Mode 1 signifies that the target will be

set manually whenever the user left-clicks somewhere within the plot. Mode -1

signifies that the target will move on its own along a predefined path. This

first function, on_button_press(), is responsible for setting the target

manually when mode is set to 1.

In matplotlib, event callbacks are defined by a function that takes an event

object as an input (whenever an event, like a button click or a key press,

occurs, this event object is sent automatically to the function). The event

object contains information about the event. In the case of a mouse click, this

includes the x and y coordinates, with respect to the plot axes, of the click,

which we obtain on lines 72-73. In the conditions on lines 77-78, we

check that we’re in the correct mode, that the button equals

“1” (“1” denotes the left mouse button), and that the

click was within the axis limits (if it wasn’t, the type of the returned

coordinates would be None instead of float). Line 81 associates the button

press event with the figure via the function on_button_press().

|

|

Next, we do the same thing for a key press event. We’d like the script to

terminate if the Enter key is pressed, by setting exitFlag to True. Moreover,

we’d like to toggle the mode if the Shift key is pressed. As above, we

check whether either of these buttons is pressed and act accordingly. On line

95, we connect the key press event to the figure.

|

|

Finally, after turning on interactive plotting and showing the plot, we employ a

while loop to continuously run our move_to_target() function. This way, the

arm will track the target any time it moves. If mode is set to -1, the target

moves in a pseudo-random fashion, which we accomplish using the continuously

changing variable t and, on lines 107-108, a few strategically placed sine

and cosine terms. I say “pseudo-random” because, of course, the

sines and cosines mean it’s actually cyclical.

The last line, line 113, is required to update the plot after button or key

press events. I utilize the figure canvas’s get_tk_widget() method

because I’m using the Tkinter backend, so this may be different if

you’re using a different backend. Tkinter is the default Python GUI

package, and allows us to create GUIs and graphical objects, like plots.

Matplotlib is able to work with a variety of different GUI backends, like GTK,

Qt, and Wx, to name a few. You can check the GUI backend currently being used

with the command plt.get_backend(). You can also list all backends available

on your system by importing matplotlib with import matplotlib followed by the

command matplotlib.rcsetup.all_backends.

Conclusion

That was a long post, but you now have a functioning script that’ll

interactively animate the Jacobian inverse technique. Try playing around with

the parameters of the inverse kinematics algorithm to see how it affects the

ability of the arm to track a target. For example, set the threshold for the

distance between the end effector and target on line 52 of

jacobianInverse.py to a value smaller than distPerUpdate and see what happens;

since you’d be setting the threshold to a value smaller than the distance

the end effector moves during each iteration of the algorithm, the end effector

might infinitely overshoot the target without being able to reach it. You can

also adjust the value by which t is incremented on line 111 to change the

speed of the target in the moving target mode.

Try adding more joints/links to the arm. An easy way to add a lot of joints in one go is with the following code:

for i in range(20):

Arm.add_revolute_link(length=3)As for interactive plotting, we’ve just barely scratched the surface. Read

the matplotlib documentation on event handling for more on the different

types of events. One idea might be to make a plot in which the arm tracks your

mouse cursor using the motion_notify_event.