Let me preface this post by saying that I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of the world of cybersecurity—I don’t claim any expertise in the field. That said, I’ve been going through the cybersecurity wargames at OverTheWire, namely the Natas wargame, which features challenges related to server-side security. The game consists of a number of levels, where each level is a password-protected webpage. The goal for each level is to leverage some security vulnerability in the webpage to obtain the password for the next level. In particular, this post deals with Natas level 11 (username: natas11, password: U82q5TCMMQ9xuFoI3dYX61s7OZD9JKoK), which simply looks like this:

The page proudly states, “Cookies are protected with XOR encryption.” XOR refers to “exclusive OR,” a logical operation that returns true when only one of its two inputs is true, and false if both inputs are true or both inputs are false. In XOR encryption, input data is encrypted by choosing a repeating key and applying a bitwise XOR operation between the key and the input.

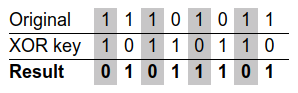

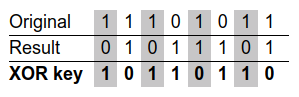

For example, suppose we wanted to encrypt the following 8 bits of data,

11101011. To encrypt our original data, we might choose a short key consisting

of 3 bits, 101. This key is repeated as many times as necessary—to

encrypt our 8 bits of data, 101, 101, 10. This would look as follows:

The encrypted result, 01011101, can be decrypted again to obtain the original

data by applying the same XOR key to the result. Returning to the Natas level 11

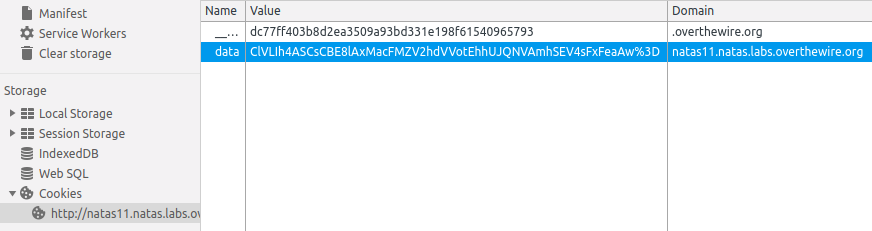

page, if we open up the browser console, we find a cookie named data:

Note that the %3D at the end of the value in the screenshot is a URL-safe

percent encoding that actually stands for the equals sign, =. Thus, the

value of the data cookie is actually

ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMZV2hdVVotEhhUJQNVAmhSEV4sFxFeaAw=. To understand what

this value means, we can look at the page source code.

<html>

<?

$defaultdata = array( "showpassword"=>"no", "bgcolor"=>"#ffffff");

function xor_encrypt($in) {

$key = '<censored>';

$text = $in;

$outText = '';

// Iterate through each character

for($i=0;$i<strlen($text);$i++) {

$outText .= $text[$i] ^ $key[$i % strlen($key)];

}

return $outText;

}

function loadData($def) {

global $_COOKIE;

$mydata = $def;

if(array_key_exists("data", $_COOKIE)) {

$tempdata = json_decode(xor_encrypt(base64_decode($_COOKIE["data"])), true);

if(is_array($tempdata) && array_key_exists("showpassword", $tempdata) && array_key_exists("bgcolor", $tempdata)) {

if (preg_match('/^#(?:[a-f\d]{6})$/i', $tempdata['bgcolor'])) {

$mydata['showpassword'] = $tempdata['showpassword'];

$mydata['bgcolor'] = $tempdata['bgcolor'];

}

}

}

return $mydata;

}

function saveData($d) {

setcookie("data", base64_encode(xor_encrypt(json_encode($d))));

}

$data = loadData($defaultdata);

if(array_key_exists("bgcolor",$_REQUEST)) {

if (preg_match('/^#(?:[a-f\d]{6})$/i', $_REQUEST['bgcolor'])) {

$data['bgcolor'] = $_REQUEST['bgcolor'];

}

}

saveData($data);

?>

<h1>natas11</h1>

<div id="content">

<body style="background: <?=$data['bgcolor']?>;">

Cookies are protected with XOR encryption<br/><br/>

<?

if($data["showpassword"] == "yes") {

print "The password for natas12 is <censored><br>";

}

?>

<form>

Background color: <input name=bgcolor value="<?=$data['bgcolor']?>">

<input type=submit value="Set color">

</form>

<div id="viewsource">[View sourcecode](index-source.html)</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Let’s break down the source code, which consists mostly of PHP. First, it

defines a variable $defaultdata, which is an array consisting of two fields,

showpassword and bgcolor. Next, it defines a function, xor_encrypt(),

which applies a bitwise XOR operation to an input and a hidden XOR key, as

described earlier, and returns the encrypted value. The array $defaultdata is

supplied to another function, loadData(), which checks to see if a cookie with

the name data has already been set. If it has, it applies several operations

to the value of that cookie via the following statement:

json_decode(xor_encrypt(base64_decode($_COOKIE["data"])), true)

From this, we can determine that the cookie’s value is first decoded from

base-64 to UTF-8 via the PHP function base64_decode(). Data is often encoded

to

base-64 for URLs and cookies, since the characters in base-64 can be

displayed on virtually every system. Next, the xor_encrypt() function is

applied to the byte string to decrypt it into a JSON string. Finally, the

built-in function json_decode() converts the JSON string to a PHP array.

That array is returned and stored in the variable $data by the line

$data = loadData($defaultdata);. The $data array is updated with a new

bgcolor from the page’s form request, if applicable, after which the

array is encrypted by the function saveData() via a process that is the

reverse of that described above. If the value of showpassword is yes, the

password is displayed on the page.

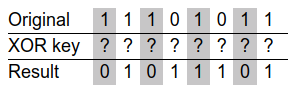

In other words, we know two things: 1) what the original unencrypted data looks

like, i.e., a JSON string of the form

{"showpassword":"no","bgcolor":"#ffffff"}, and 2) what the resulting encrypted

cookie looks like, i.e.,

ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMZV2hdVVotEhhUJQNVAmhSEV4sFxFeaAw=. Our goal is to

determine the XOR key so we can create our own encrypted cookie with the value

of showpassword set to yes. If this were our original simplified example, we

would have the following situation:

In fact, with this information, obtaining the repeating XOR key is a trivial matter of computing the bitwise XOR of the encrypted result with the unencrypted original data:

By inspection, we can (hopefully) determine that the original XOR key is 101.

Once we have the original XOR key, we can fabricate our own original data, apply

the XOR key to encrypt it, and spoof a valid cookie.

How do we actually accomplish that with the Natas level 11 webpage and cookie? I wrote a little PHP script to compute the bitwise XOR of the original unencrypted data (encoded to a JSON UTF-8 string) and the encrypted cookie (decoded from base-64 to a UTF-8 string):

<?php

$data = array("showpassword" => "no", "bgcolor" => "#ffffff");

$cookie = "ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMZV2hdVVotEhhUJQNVAmhSEV4sFxFeaAw=";

$repeated_xor_key = json_encode($data) ^ base64_decode($cookie);

echo $repeated_xor_key;

?>

Running this on a PHP-enabled server yields the following repeated XOR key:

qw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jqw8Jq

By inspection, it’s clear that the XOR key is qw8J, which we can verify

by encrypting the original unencrypted data and comparing it to the original

encrypted cookie (or vice versa). With the XOR key now in our hands, we can

create our own encrypted cookie with showpassword set to yes. To do so,

let’s write a modified version of the xor_encrypt() function from the

webpage source code and apply the XOR key we’ve discovered:

<?php

function xor_encrypt($data, $key) {

$out = "";

for ($i = 0; $i < strlen($data); $i++) {

$out .= $data[$i] ^ $key[$i % strlen($key)];

}

return $out;

}

function encrypt($data, $key) {

return base64_encode(xor_encrypt(json_encode($data), $key));

}

$data = array("showpassword" => "yes", "bgcolor" => "#ffffff");

$key = "qw8J";

$spoofed_cookie = encrypt($data, $key);

echo $spoofed_cookie;

?>

Running this yields the following spoofed cookie value:

ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMOXTlTWxooFhRXJh4FGnBTVF4sFxFeLFMK

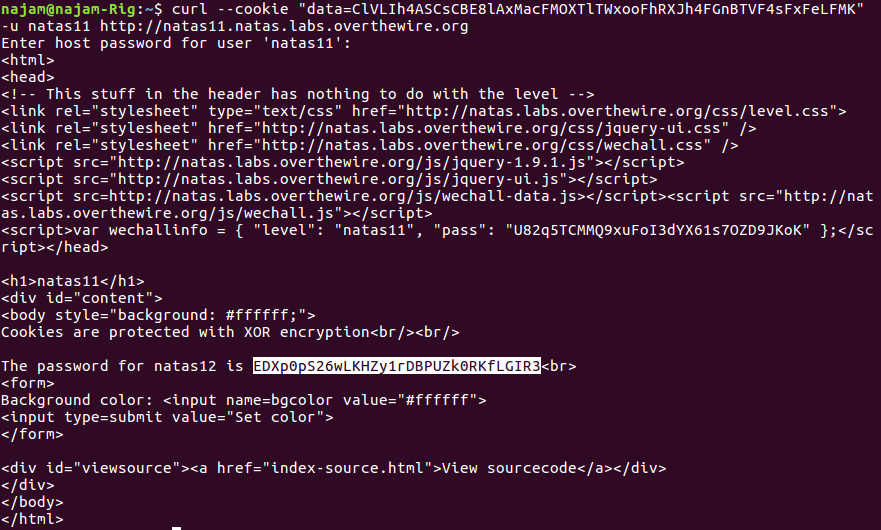

Lastly, to access the webpage with the spoofed cookie, we can open up a terminal

and send the request via curl:

$ curl --cookie "data=ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMOXTlTWxooFhRXJh4FGnBTVF4sFxFeLFMK" -u natas11 http://natas11.natas.labs.overthewire.orgThis returns the following response:

Success! The password for the next level is highlighted in the screenshot above.

Obtaining the key by brute force

Of course, this got me thinking about the case where we don’t know what the original data looks like. So, I wrote a Python script to aid in this task.

import base64

import itertools

import json

import time

def xor_encrypt(data, key):

out = []

for i in range(len(data)):

xor = ord(data[i]) ^ ord(key[i % len(key)])

out.append(chr(xor))

return "".join(out)

def decrypt(data, key):

return json.loads(xor_encrypt(base64.b64decode(data).decode("utf-8"), key))

def bruteforce(encrypted_data, min_key_len=1, max_key_len=1):

chars = [chr(i) for i in range(48, 123)]

keys = []

start_time = time.time()

for key_len in range(1, max_key_len + 1):

print("[{} s] Trying key length ".format(time.time() - start_time)

+ str(key_len))

for product in itertools.product(chars, repeat=key_len):

key = "".join(product)

try:

decrypt(encrypted_data, key)

except:

continue

else:

keys.append(key)

print("[{} s] Completed".format(time.time() - start_time))

return keys

def test_keys(encrypted_data, keys):

for key in keys:

decrypted_str = str(decrypt(encrypted_data, key))

if decrypted_str[0] == "{" and decrypted_str[-1] == "}":

return key

if __name__ == "__main__":

cookie = "ClVLIh4ASCsCBE8lAxMacFMZV2hdVVotEhhUJQNVAmhSEV4sFxFeaAw="

keys = bruteforce(cookie, max_key_len=4)

key = test_keys(cookie, keys)

if key:

print("Key: " + key)

print("Decrypted data: " + str(decrypt(cookie, key)))

else:

print("No key found")The function xor_encrypt() performs the same task as its PHP counterpart, and

decrypt() is the inverse of encrypt(). The function bruteforce()

constructs a XOR key from a range of

ASCII characters—I’ve arbitrarily chosen characters from

“0” (ASCII code 48) to “z” (ASCII code 122). This is

done for a number of key lengths: a key one character long would include keys

“0”, “1”, …, “y”, “z”; a

key two characters long would include keys “00”, “01”,

…, “zy”, “zz”, and so on. The decrypt() function

is called on each key—however, most keys will not produce a valid sequence

of UTF-8 encoded bytes. Only valid byte sequences are added to a list, keys,

which the function returns.

The function test_keys() makes an assumption about the original unencrypted

data, namely that it’ll be a JSON string that begins and ends with curly

braces ({ and }). It takes a list of potentially valid keys and returns the

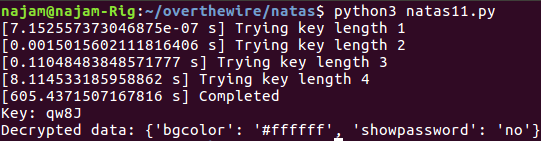

one (if any) that produces a decrypted JSON string. Running the script for keys

up to four characters in length produces a successful result:

How validating! Of course, this approach has obvious limitations, namely the fact that I chose an arbitrary subset of ASCII/UTF-8 characters with which to construct the key and the fact that I’m assuming the decrypted data will be human-readable and a JSON string.

However, what makes this approach most untenable is that it’s a brute force approach with exponential time complexity, i.e., \(O(k^n)\), where \(k\) is the number of choices for each character of the XOR key and \(n\) is the length of the key. In fact, because my function tracks and displays the amount of time it takes to try all possible keys for a given key length, we can see this in action. Per the screenshot above, it took approximately:

- 0.0015 seconds to try all 1-character key combinations

- 0.11 seconds to try all 2-character key combinations

- 8.0 seconds to try all 3-character key combinations

- 600 seconds to try all 4-character key combinations

Because I’ve limited the choice of characters to 75 (ASCII codes 48 to 122), that means there are \(75^1 = 75\) possible 1-character keys, \(75^2 = 5625\) possible 2-character keys, \(75^3 = 4121875\) possible 3-character keys, \(75^4 = 31640625\) possible 4-character keys, and so on. In fact, if we divide the number of 1-character keys by the time it took to try all those keys, we can see how accurate this is. If it took 0.0015 seconds for 75 keys, that’s a rate of 0.00002 seconds per key. Based on this, it should take \(0.00002 \times 75^2 = 0.11\) seconds to try all 2-character keys, \(0.00002 \times 75^3 = 8.4\) seconds to try all 3-character keys, and \(0.00002 * 75^4 = 633\) seconds to try all 4-character keys. These numbers are almost exactly what I got above. Then, to try all 5-character keys, it would take my system about 47500 seconds, which is about 13 hours, and to try all 6-character keys, 3.56 billion seconds, which is 41 days. Hence, a XOR key of decent length can quickly become impossible to brute force.

There are techniques to reduce the search space for decrypting XOR-encrypted data, as well as non-brute force approaches that avoid some of the aforementioned pitfalls, but I’m not well-versed on these. Seems like there’s a lot left to learn.