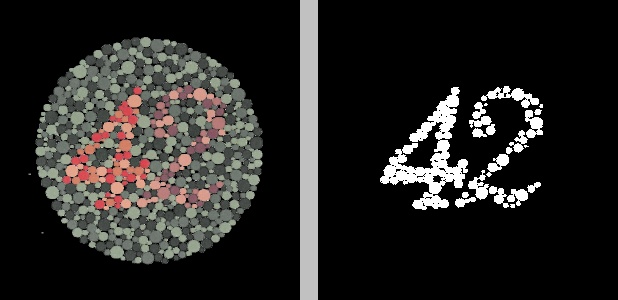

The previous post discussed the use of K-means clustering and different color spaces to isolate the numbers in Ishihara color blindness tests:

In the figure above, the original image on the left was converted to the YCrCb color space, after which K-means clustering was applied to the Cr channel to group the pixels into two clusters. The result is the image on the right, where black represents one cluster and white represents the other cluster.

In this post, we’ll go through the Python code that produced this figure (and the other figures from the previous post) using OpenCV and scikit-learn.

The code

The

script can be found on my github, if you’re so inclined. Otherwise,

fire up a text editor and create a file named color_segmentation.py.

|

|

First, the necessary imports. The datetime module will be used to construct a

unique timestamped filename for the output image.

|

|

Next, we construct the argument parser to handle input options and parameters. The usage of each flag can be seen from its respective help text above and should also become more clear as we go through the rest of the code.

|

|

Line 25 puts the input arguments into a dictionary args. Line 26 reads

the input image and stores it in image. If a width was specified by the user,

lines 29-32 resize the image using the OpenCV function resize(). At this

stage, we create a copy of the image on line 33 since we’ll continue

to modify the image (this allows us to use or display the original later).

|

|

Next, the image is converted to the desired color space, if the user specified

one, using OpenCV’s cvtColor() function. Note that OpenCV utilizes the

BGR color space by default, not RGB, when it reads in an image with

cv2.imread() or displays a color image with cv2.imshow().

|

|

Now that the image has been converted to the correct color space, we’ll

isolate only the channels on which we wish to perform K-means clustering. The

channels input argument takes a string of digits, where each digit represents

a channel index. For example, in the BGR color space, channel 0 would be B (the

blue channel), 1 would be G (the green channel), and 2 would be R (the red

channel). Similarly, if we’d converted the image to the YCrCb color space,

0 would denote channel Y (luma), 1 would denote channel Cr (red-difference), and

2 would denote channel Cb (blue-difference). For example, a user input of

“01” would mean we wish to use channels 0 and 1 for K-means

clustering. An input of “2” would mean we wish to use only channel 2

for K-means clustering. If only a single channel is selected, the resulting

numpy array loses its third dimension (an image array’s first index

represents the row, its second index represents the column, and the third index

represents the channel). Lines 53-54 check for this and simply

“reshape” the array by adding a dummy third index of length 1, if

necessary, so the array works with the upcoming code.

|

|

The scikit-learn K-means clustering method KMeans.fit() takes a 2D array whose

first index contains the samples and whose second index contains the features

for each sample. In other words, each row in the input array to this function

represents a pixel and each column represents a channel. We achieve this by

reshaping the image array on line 58. Lines 61-62 ensure that a value of

at least 2 clusters was chosen (since classifying the pixels into a single

cluster would be meaningless).

Line 64 actually applies K-means clustering to the input array.

KMeans(n_clusters=numClusters, n_init=40, max_iter=500) creates a KMeans

object with the given parameters. n_init=40 means that K-means clustering will

be run 40 times on the data, with the initial centroids randomized to different

locations each time, from which the best result will be returned. 40 isn’t some

universal magic number—I simply tried a few different values and found it

to be the lowest value that provided consistent results. max_iter=500 means

that, during each of those 40 runs, the cluster centroids will be updated until

they stop changing or until the algorithm has continued for 500 iterations.

Again, 500 isn’t a magic number. I simply found it to provide the most

consistent results. fit(reshaped) actually runs the algorithm using these

parameters on our dataset.

|

|

After running the K-means clustering algorithm, we retrieve the cluster labels

using the labels_ member array of the KMeans object. We reshape this back

into the image’s original 2D shape on lines 68-69.

Since we’re going to display the clustered result as a grayscale image, it makes

sense to assign hues (black, white, and as many shades of gray in between as are

necessary) to the clusters in a logical order. The cluster labels won’t

necessarily be the same each time K-means clustering is performed, even if the

pixels in the image are grouped into the same clusters—e.g.,

KMeans.fit() might, on one run, put the pixels of the number in a color

blindness test into cluster label “0” and the background pixels into cluster

label “1”, but running it again might group pixels from the number into cluster

label “1” and the background pixels into cluster label “0”. However, assuming

the pixels are clustered the same way each time (even if the clusters end up

with different labels), the total number of pixels in any given cluster

shouldn’t change between runs. Lines 72-73 exploit this by putting the

cluster labels in a list sorted by the frequency with which they occur in the

clustered image, from most to least frequent.

|

|

Finally, we create a single-channel 8-bit grayscale image where each pixel is

assigned a hue based on the cluster to which it belongs and the frequency of the

cluster (from the sorted list of labels). In an 8-bit grayscale image, a pixel

with a value of 0 is black and a pixel with a value of 255 is white, which is

where 255 comes from on line 78. At this point, we could stop and display

the grayscale image with a call to cv2.imshow(). For convenience, though,

let’s put the original image and the resulting clustered image, kmeansImage,

side by side:

|

|

Since we want to show the original BGR image alongside the clustered grayscale

image, we have to convert the grayscale image to BGR. For clarity, I’ve opted to

add a strip of gray between the two images, whose hue is given by the arbitrary

value 193, whose height is the same as that of the images, and whose width I’ve

defined as a percentage (6.25%) of the image width. The original image, gray

divider, and clustered image are stacked horizontally with a call to the numpy

function concatenate().

|

|

Lastly, if the user supplied the --output-file option, lines 86-93

construct a timestamped filename that contains the name of the chosen color

space, the channel indices, and the number of clusters used for clustering, then

write the image to disk with a call to cv2.imwrite(). Line 94 waits until

any key is pressed to close the window previously displayed by cv2.imshow().

Usage

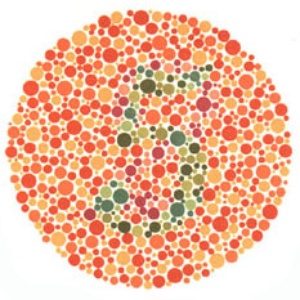

Say we had the following source image, named ishihara_5_original.jpg:

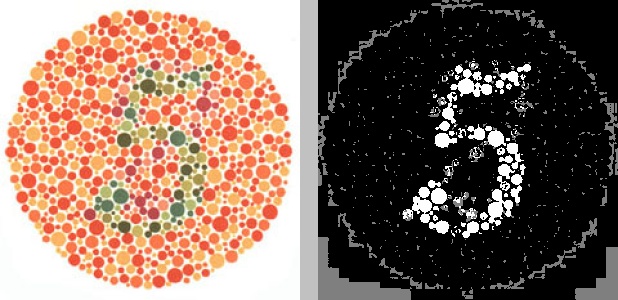

We might run the following in our terminal or command line window:

python color_segmentation.py -i ishihara_5_original.jpg -w 300 -s hsv -c 02 -n 3 -o -f jpgThis translates to “resize the source image ishihara_5_original.jpg

(-i ishihara_5_original.jpg) to a width of 300 pixels (-w 300), convert it

to the HSV color space (-s hsv), then perform K-means clustering on channels 0

and 2 (-c 02) by grouping the pixels into 3 clusters (-n 3) and output the

resulting file (-o) in JPG format (-f jpg). " The result would look like

this:

The resulting filename of the output image would be something like

2018329194036hsv_c02n3.jpg. Recall from the beginning of the file that all

arguments except the source image filename are optional, though the defaults

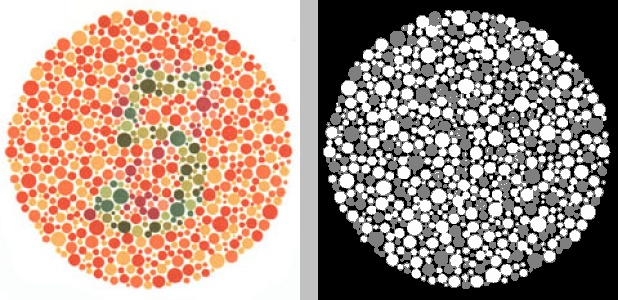

won’t necessarily provide optimal clustering. For example, this is what happens

if we just run it with the default settings—BGR color space (equivalent to

specifying the option -s bgr), all channels (equivalent to specifying -c 012

or -c all), and 3 clusters:

python color_segmentation.py -i ishihara_5_original.jpg -w 300

Try the script on your own images, or tweak it to your liking.