While I’m not a chemist, I am one of those unusual people who enjoyed organic chemistry in college. Lately, I’ve been reading up on the periodic table on Wikipedia (who among us doesn’t do this every 6-8 weeks?) and thought it would be interesting to develop a concise equation or program to directly determine the atomic number \(Z\) of the \(k^\text{th}\) noble gas, including hypothetical noble gases that don’t exist. I claim no practical use for this exercise other than it seemed fun and somewhat educational. Chemistry-averse readers need not fear; this post is more about patterns and sums than about chemistry.

The noble gases, so named because they are largely chemically inert, are the elements in the last group (last column) of the periodic table. Their general lack of chemical reactivity is due to their electron configuration, which comprises full, stable outer shells. The existing elements of this group (helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon, radon, and oganesson) are listed in the table below, along with their atomic numbers \(Z\) and chemical symbols. The index \(k\), which appears in the title, is simply a variable I came up with to describe the location of each noble gas in the sequence. \(k=1\) refers to helium since it’s the first noble gas, \(k=2\) refers to neon since it’s the second noble gas, \(k=3\) refers to argon since it’s the third noble gas, and so on.

Table 1. Noble gases

| $$\mathbf{k}$$ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | … | |

| Symbol | – | He | Ne | Ar | Kr | Xe | Rn | Og | … |

| $$\mathbf{Z}$$ | 2 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 54 | 86 | 118 | … | |

| $$\mathbf{\Delta Z}$$ | – | 2 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 18 | 32 | 32 | … |

The table above also includes a row labeled \(\Delta Z\), a quantity I use to describe the difference between the atomic number \(Z\) of each element in the sequence with the previous element in the sequence. For example, xenon (\(k=5\)) has atomic number \(Z=54\) and the previous element in the sequence, krypton (\(k=4\)), has atomic number \(Z=36\). \(54 – 36 = 18\), so the value of \(\Delta Z\) corresponding to xenon (\(k=5\)) is 18. For the seven elements above, we can find the sequence of \(\Delta Z\) values to be 2, 8, 8, 18, 18, 32, 32. Remember this sequence—it’s important and will come up again.

The atomic number of an element is equal to the number of electrons surrounding the atom. Thus, the atomic number is directly related to the element’s electron configuration. The electrons of an atom are grouped into shells, specifically into subshells within each shell. Each shell is described by the principal quantum number \(n\). \(n=1\) would refer to the first shell, \(n=2\) would refer to the second shell, and so on. Each shell has \(n\) possible subshells, so the first shell (\(n=1\)) has 1 subshell, the second shell (\(n=2\)) has up to 2 subshells, the third shell (\(n=3\)) has up to 3 subshells, and so on. Subshells are described by the azimuthal quantum number \(l\), which begins at \(l=0\). Electrons fill shells and subshells in order of increasing energy, the details of which are beyond the scope of this post.

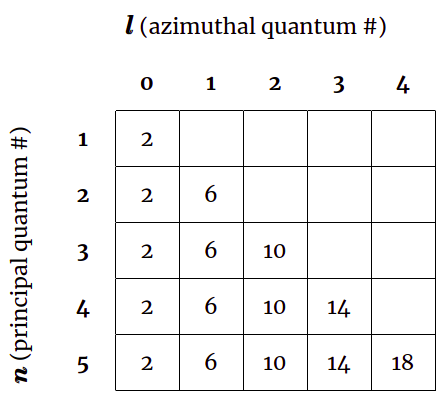

Each subshell \(l\) can hold up to \(2(2l+1)\) electrons, meaning that the first subshell (\(l=0\)) contains up to 2 electrons, the second subshell (\(l=1\)) contains up to 6 electrons, the third subshell (\(l=2\)) contains up to 10 electrons, etc. You might know subshells by their more familiar letter designations: \(s\), \(p\), \(d\), and \(f\), where \(l=0\) corresponds to \(s\), \(l=1\) corresponds to \(p\), and so on. The table below displays the subshells (and the maximum number of electrons in each) for the first five shells.

Table 2. Shells and subshells

The first shell (\(n=1\)) has one subshell and a total of 2 electrons. The second shell (\(n=2\)) has two subshells containing up to 2 + 6 = 8 electrons. The third shell (\(n=3\)) has three subshells containing up to 2 + 6 + 10 = 18 electrons. The fourth shell (\(n=4\)) has four subshells containing up to 2 + 6 + 10 + 14 = 32 electrons. Observe how these numbers—2, 8, 18, 32—are the same as the values from the \(\Delta Z\) row in Table 1. Remembering that there are \(2(2l+1)\) electrons in a subshell \(l\) and that a shell \(n\) has \(n\) subshells (numbered from \(l=0\) to \(l=n-1\)), we can write the total number of electrons \(e_n\) in the \(n^{\text{th}}\) shell as the sum of its subshells:

\(\displaystyle e_n = \sum\limits_{l=0}^{n-1} 2(2l + 1)\)

Multiplying this out and evaluating the sums:

\(\displaystyle e_n = \sum\limits_{l=0}^{n-1} {2(2l + 1)} = 4\sum\limits_{l=0}^{n-1} {l} + \sum\limits_{l=0}^{n-1} {2}\)

\(\displaystyle \:\:\:\:\:\: = 2n(n-1) + 2n\)

\(\displaystyle e_n = 2n^2\) (Equation 1)

Thus, there can be up to \(2n^2\) electrons in each shell, which corresponds to the values of 2, 8, 18, 32, etc. Next, referring again to Table 1, notice how we can split the elements into pairs with identical \(\Delta Z\) values. For example, \(k=0\) and \(k=1\) would form the first pair. The second pair would include \(k=2\) and \(k=3\), both of which have \(\Delta Z = 8\). The third pair would consist of \(k=4\) and \(k=5\), which have \(\Delta Z = 18\). The fourth pair would be \(k=6\) and \(k=7\), which have \(\Delta Z = 32\). The only exception is the first pair with \(k=0\), since that doesn’t correspond to an actual element with a positive number of electrons, but the pattern remains otherwise unaffected. Let’s number these pairs using the letter \(p\). The first pair, \(p=1\), would contain \(k=0, 1\). The second pair, \(p=2\), would contain \(k=2, 3\). You get the idea.

The first important thing to recognize here is that each pair has the same \(\Delta Z\) value, as we just mentioned, and that the \(\Delta Z\) value for each pair is the same as that given by Equation 1 above. In fact, let’s just replace the \(n\) in that equation with the pair \(p\):

\(\displaystyle \Delta Z_p = 2p^2\) (Equation 2)

The second important thing to recognize is that the atomic number \(Z\) for the \(k^\text{th}\) element is equal to the sum of all the \(\Delta Z\) values up to and including that element, which makes sense. For example, the atomic number for xenon (\(k=5\)) is equal to 2 + 8 + 8 + 18 + 18 = 54.

Each pair has two elements (by definition), which means that with each pair, we add \(2\Delta Z_p\) electrons to the total. Again, the first pair is an exception, but we’ll get to that. Consider the second pair, for example (\(k=2, 3\)), which has \(\Delta Z_2 = 8\) for each element. Taken together, this pair adds 2 * 8 = 16 electrons to the total. The third pair (\(k=4, 5\)) has \(\Delta Z_3 = 18\) and adds 2 * 18 = 36 electrons to the total. Then the sum of the first \(P\) pairs is given by:

\[\text{sum of first } P \text{ pairs} = \left(\sum\limits_{p=1}^{P}2(2p^2)\right) - 2\]

We subtract 2 to account for the fact that \(k=0\) (from the first pair) doesn’t actually contribute 2 electrons to the total. From Faulhaber’s formula for sums of polynomial sequences, we can rewrite the sum of the quadratic sequence above as a nice cubic polynomial:

\(\displaystyle \text{sum of first } P \text{ pairs} = \left(\frac{2P(P+1)(2P+1)}{3}\right) - 2\)(Equation 3)

This simplifies things considerably. Then the problem becomes a matter of following these steps:

- Choose the value of \(k\).

- Determine which pair \(p\) the chosen value of \(k\) belongs to.

- Compute the sum of all previous pairs (up to pair \(p-1\)) using Equation 3.

- Compute \(\Delta Z_p\) for the current pair \(p\) using Equation 2.

- Add either \(\Delta Z_p\) to the subtotal from step 3 (if \(k\) is the first element of pair \(p\)) or \(2\Delta Z_p\) (if \(k\) is the second element of pair \(p\)).

For step 2, the pair to which \(k\) belongs is equal to 1 plus the integer division of \(k\) into 2, i.e.:

\[p = (k \text{ div } 2) + 1\]

Integer division refers to dropping anything beyond the decimal point and keeping only the whole numbers after division, e.g., \(3 \text{ div } 2 = 1\). The second to last pair \(p-1\) is simply the equation above minus 1:

\[p - 1 = (k \text{ div } 2)\]

For step 5, we can determine whether \(k\) is the first or second element of pair \(p\) with modulo division, which yields the remainder after a division operation, i.e., \((k \text{ mod } 2)\). This yields 0 if \(k\) is even (making it the first element of the pair) or 1 if it’s odd (making it the second element of the pair). Putting it all together:

\[Z_k = \left(\frac{2(k \text{ div } 2)((k \text{ div } 2) + 1)(2(k \text{ div } 2) + 1)}{3}\right) - 2 + ((k \text{ mod } 2) + 1)(2((k \text{ div } 2) + 1)^2)\]

The term \(2((k \text{ div } 2) + 1)^2\) at the end corresponds to Equation 2, i.e., \(2p^2\), and the preceding multiplier \((k \text{ mod } 2) + 1\) determines whether it should be added once or twice (\(\Delta Z_p\) or \(2\Delta Z_p\)) based on the result of the modulo division.

And that’s it! A method for directly obtaining the atomic number of the \(k^{\text{th}}\) noble gas. How might we implement this in code? Here’s an example in the form of a short Python function.

def noble(k):

prev_pairs = int((2 * (k // 2) * (k // 2 + 1) * (2 * (k // 2) + 1)) / 3) - 2

return prev_pairs + ((k % 2 + 1) * 2 * (k // 2 + 1)**2)Perhaps cryptic for someone who hasn’t read this post and doesn’t know how it was derived, but otherwise fairly straightforward.

Practical considerations

Like I said at the beginning of this post, there is little practical use for this—there are currently only a handful of elements in the noble gas group. As of this writing, no elements beyond 118 (oganesson) have been synthesized. This is because elements with high atomic numbers tend to be extremely unstable and live for only small fractions of a second (according to IUPAC, an atom of an element must survive for at least 10-14 seconds to be considered to exist—this is the amount of time required to form an electron cloud). It’s doubtful that noble gas \(k=8\) (atomic number 168) could even exist, much less \(k=9\) (atomic number 218). Even if atoms of these elements could exist, the quantum effects resulting from large nuclei and large electron clouds would affect the properties of these elements. I won’t pretend to understand quantum chemistry or atomic forces, but these effects basically mean that superheavy elements may not follow the same trends as elements with lower atomic numbers—in other words, element 168 would not necessarily behave like a noble gas. In fact, the Wikipedia article on the extended periodic table theorizes that, in terms of behavior, element 172 would be the next noble gas (or “noble liquid,” more accurately), due to these effects.

Still, it’s an interesting exercise in sums and patterns that showcases some of the periodicity of the periodic table.